Vegetable Gardening in Communal Amana

Feb 9, 2015

If you have a vegetable garden, you know how wonderful those veggies taste when they're whisked out of the garden and onto the table in less than an hour or so. Imagine the coordinated effort it would take to accomplish that for an entire village. The Amana settlers did just that and did it well.

BEGINNINGS

In 1856, the first of a group of 1,200 German Inspirationists from Ebenezer, New York, arrived in the Iowa River valley in eastern Iowa to make their new communal home. They chose an ideal site with the help of local Native Americans who accompanied them in their search and gave them advice. The soil was extremely fertile, the bluffs above the river valley were heavily wooded, there were sandstone outcroppings for quarrying, and clay deposits suitable for brick-making. Calling itself the Amana Society, the new community would prosper, ultimately erecting seven villages on their 26,000 acre tract of land: Amana (the main and original village), East Amana, High Amana, Middle Amana, South Amana, West Amana, and Homestead. The latter was already in existence and had already been named when the Amana Society bought it. (More history: http://www.amanacolonies.com/history-of-amana/)

LIFE IN THE AMANAS

The church elders in the Amanas (as the villages are called collectively) reigned supreme over both the secular and religious affairs of the villages. Residents were assigned living quarters, ate in communal kitchens, and worked daily--with the exception of Sundays--at their assigned tasks. Each village had its own church, farm fields, farm animals, orchards, vineyards, kitchen gardens, school, bakery, dairy, wine cellar, post office, sawmill, and general store.

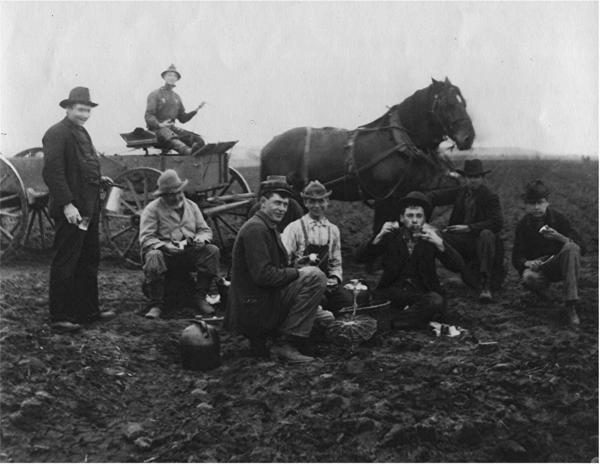

A typical day in the life of Amana Society residents began with breakfast at the communal kitchen to which they were assigned. Then it was off to the assigned tasks for the day. That might be preparing the rest of the daily meals, hauling manure to the fields; planting and tending crops; making baskets, tinware, or pottery; smoking meats; tailoring clothes; doing leather work; making cherry and walnut furniture; or working in the woolen and flour mills or in the calico factory. There was generally a work- and food break at mid-morning and again after the noon meal at mid-afternoon. During the growing season, workers in the fields got special attention from the kitchen ladies, who prepared tasty snacks to sustain them for the rest of their work day. The food was delivered by horse and wagon to the laborers wherever they happened to be located in the fields.

After the evening meal, the day was not yet over. Prayer meetings were held every evening at various locations around each village. There were also religious services in the main church building on Wednesday and Sunday mornings (and sometimes in the afternoons). Not counting religious holiday observances, there were generally eleven services in each village every week.

KITCHEN GARDENS

The Society raised almost all of its own food. To that end, kitchen gardens were an especially important component of village life. Each kitchen was assigned a plot of land (usually two or three acres) on which to raise its produce. Villages had anywhere from three to twelve communal kitchens, depending on the size of the village. In all, about 100 acres were devoted to raising produce within the commune.

While the communal kitchen was the purview primarily of the younger women, older women were assigned to work in the kitchen gardens. For each garden there was a "Gartebaas" ("Garden Boss"), one of the older women who was well-versed in the raising of produce and oversaw all aspects of communal gardening on her plot of land. Several women worked in each garden, raising an astounding assortment of vegetables and other produce (See listing at the end of this article).

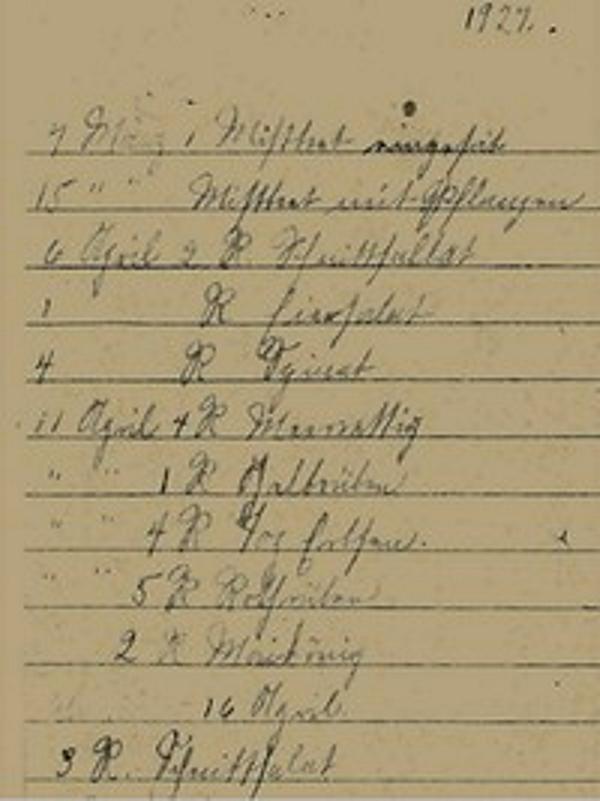

Along with growing and harvesting crops, the kitchen garden boss was responsible for saving seeds from each crop and scheduling its planting during the next growing season. She kept a planting schedule in a gardening journal for easy reference.

The rectangular cold frames in the garden plots were constructed of four sections of wood planks approximately one foot high. Since wooden storm windows were used as frame covers, the frames were built to accommodate them. The windows measured approximately 28 inches by 58 inches and were placed on the frames in mid-February so that the soil would thaw out and dry a bit if wet. Once the soil could be worked, compost was added, the soil was raked and leveled and made ready for sowing. Seeds were sown in marked rows. Old carpeting was draped over the windows on particularly cold nights to keep heat from escaping. When the weather was warm, the window covers were propped open with a block of wood for ventilation.

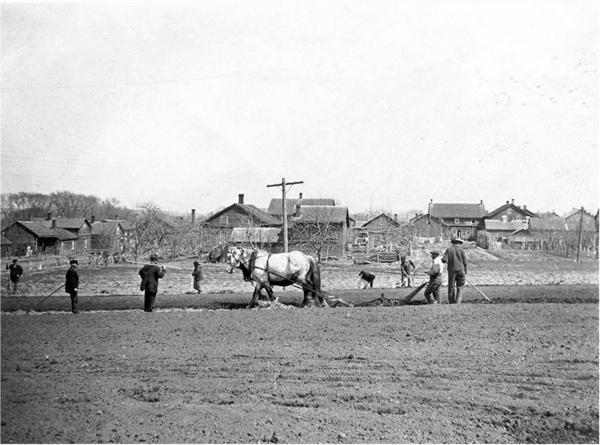

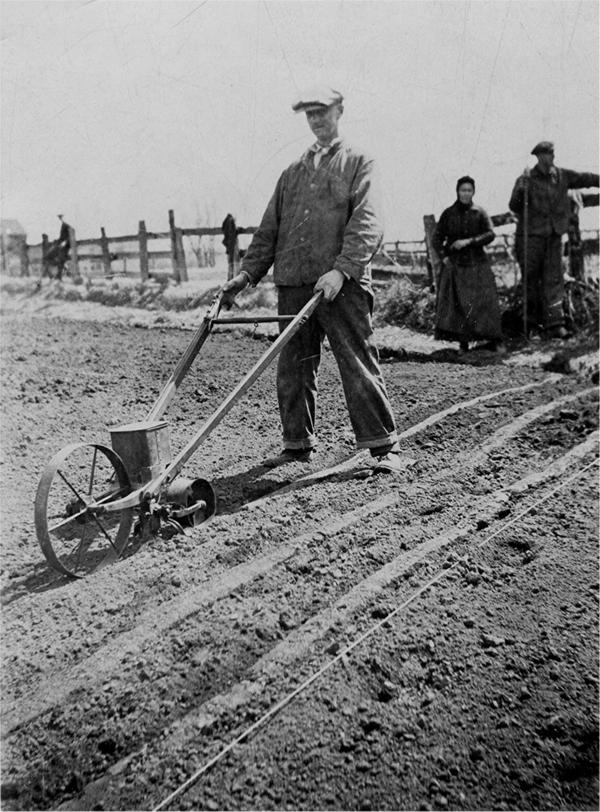

Once the weather warmed to the point where planting in the garden could begin, farm workers tilled it with a horse-drawn plow, raked it smooth, and fertilized it with manure from the village stables and barnyards. The women trampled paths into the soil with their feet and prepared rows for sowing and planting. Both of these activities were accomplished with the help of string stretched taught as a guideline, so that the rows and pathways would be perfectly straight, a testimony to the German penchant for Ordnung ("proper order").

THE END

Communal gardening and dining in the Amanas came to an abrupt halt in May of 1932. On June 1st of that year, the old order passed away. A new, far more secular society was born, when over 90% of the members voted to form a joint stock corporation organized for profit. How did such an about face come to pass? There are many reasons. They fall into three broad categories:

- Loss of charismatic leadership

- Gradual abandonment of the philosophy of isolation from the outside world.

- Financial problems aggravated by social unrest locally and a deepening economic depression nationally.

As long as the commune was isolated from the outside world by decree, by language, by religion, and by social customs, its culture flourished. That isolation would gradually break down with the coming of new technology: the railroad, the automobile, the car, the radio, and the telephone. By the 1920s, the outside world was flocking to the Amanas, with their quaint buildings and people, their beautiful, bucolic setting, and that wonderful food in the communal kitchens, served free to visitors. In the end, the residents of the Amana Society wanted to be part of that fascinating, larger world.

The Amanas today are bustling with activity of all kinds. The arts (notably painting, using various media) have blossomed in the post-communal era as have music and numerous crafts. I find it amazing that so many artistic talents had lain dormant in communal Amana and now have found their expression in the post-1932 culture. The countryside in this lush river valley remains as beautiful as ever. All pastures and forestland owned by Amana Society, Inc., comprise a game preserve that supports a wealth of plant and animal life. And those good old communal kitchen garden dishes still grace many an Amana kitchen table at mealtime.

Below is a list of all vegetable varieties grown and how they were used or stored.

Asparagus

Planted in beds; young shoots usually harvested until early June; served cooked and creamed

Beans

Planted around poles; approximately one bushel per kitchen house meal; excess (1) blanched and dried for winter use, (2) canned, (3) pickled

Cabbage

Sown in cold frames; set out in rows; harvested by the wagonful; shredded and fermented; surplus shipped to markets in Chicago; full heads stored in kitchen house earthen basements for winter use

Carrots

Sown in rows; harvested in fall; some left in ground to go to seed the 2nd year; eaten raw, cooked, and pickled; some stored in basements

Cauliflower

Sown in cold frames; set out in rows; also sowed in late summer and harvested in fall; leaves tied over heads to prevent bitterness; eaten creamed

Celeriac (type of celery with bulbous root) Sown in cold frames; set out in rows; used extensively in soups; bulbs stored in basements

Celery

Sown in cold frames; set out in rows; shaded with boards or newspaper to blanch stalks and prevent bitter taste; stored in basements

Chives

Clumps planted in beds and propagated by division; chopped leaves used as flavoring

Citron (melon)

Sown in hills after danger of frost; unpalatable raw; flesh cut in slivers and pickled

Corn (sweet)

Planted in rows in fields and raised the same way as field corn

Cucumbers

Planted in hills after danger of frost; eaten as salad or pickled in large crocks for winter consumption

Dandelion

Early spring greens collected in the wild; sometimes raised in gardens and blanched like celery to prevent bitter flavor; eaten as salad with creamy dressing and chopped boiled egg

Dill

Sown in beds (will also reseed); used to flavor pickled beans and cucumbers; dried seed also used as flavoring

Endive (member of lettuce family)

Sown in beds or rows; blanched like lettuce when it began to mature; used in salads

Ground Cherry (actually related to the tomatillo)

Grown in beds and rows; reseeds prolifically; fruit inside husk was used in pies and jams

Horseradish

Planted in rows; propagated by rootlets overwintered in basements; mature roots were scraped and ground into a condiment or chopped, cooked, and creamed as a vegetable; roots stored in basements

Kale

Sown in cold frame; set out in rows; leaves dried; reconstituted and served creamed in winter; surplus fed to chickens

Kohlrabi (bulbous stem)

Sown in cold frames; set out in rows; sown again in summer for fall crop; eaten cooked and creamed; fall crop stored in basements

Lettuce (loose heads)

Sown directly into beds; served as salad with creamy dressing and chopped boiled egg

Onions*

Sown/planted in rows; raised in large fields; three-stage process: Seed obtained from mature onions; seed produces sets; sets planted next year produce mature onions; used in cooking customary vegetable and meat dishes; mature onions stored in basements

Peas

Sown in rows; creamed when served fresh; rest dried for winter use

Potatoes*

Planted in large fields; eyes cut from mature potatoes planted in rows; plowed out in fall; served daily in some form at each of the three main meals; stored in church basement

Pumpkins

Sown in hills after danger of frost; harvested in fall and used in pies; stored in basements

Radishes

Sown in rows or beds; specimens for seed were transplanted; served as a salad or raw; harvested in spring and fall; stored in basements

Salsify (root crop)

Sown in rows; roots dug in fall; chopped and served as creamed vegetable; stored in basements or left in ground to over-winter

Spinach

Sown in beds; cooked and ground when served fresh with beef stock and onion; blanched in hot water and hung to dry in kitchen attics for winter use

Tomatoes

Sown in cold frame; set out in rows; eaten fresh, canned or made into ketchup

Turnips

Sown in rows in August; served cooked and creamed; stored in basements

*The Society also raised onions (both seed and bulbs) and potatoes in very large quantities as a cash crop and sold them on the market, generally in the Chicago and Milwaukee areas. School children were recruited to help with the harvest. These crops, along with sweet corn, were grown and harvested under the guidance of the village farm manager and his crew.

All photos courtesy of Amana Heritage Museum